Why is it that movies like Shakespeare in Love, Romeo and Juliette (with Leonard DiCaprio and Clair Danes), 10 Things I Hate About You, She’s the Man, and other films about the Bard and his plays are so popular when so many students dread the word “Shakespeare”? Tell a class of students they will be reading a play, and you will hear groans that would make you think the cafeteria had given everyone food poisoning. But, make a hit television show like House of Cards that is full of characters and situations from Macbeth, and you will make millions. It begs the question, how do you teach students to read Shakespeare’s texts without traumatizing them? Clearly, the content of the plays is enjoyable, so how to you circumnavigate the language?

When I was an undergrad, I did a senior project that attempted to answer that question. Over my tenure in the classroom, I’ve built on that initial research and have what I believe is a very successful approach to teaching these texts even at the middle school level. The answer is don’t circumnavigate the language, teach it; teach it like a foreign language so that the students can read it and understand it. Impossible, you say? Poppy cock!

Below is a concise “Introduction” to my revised “How to Teach Shakespeare” research. In college, it was titled “A Method to the Madness,” a paraphrase we steal from Shakespeare. I’m not going to post my entire project, but occasionally, I would like to share my teaching techniques in the hopes that others may be able to use them in their English classrooms.

Shakespeare’s plays are staples of English curricula at all levels around the country. And while English teachers relish these texts, students often approach the plays with hesitation or even distaste. Reading Shakespeare is unquestionably difficult, but it should not be painful.

This is a list of activities, projects, and methods teachers can use when they are addressing a Shakespearean play. I have used these ideas for the last five years with three different Shakespearean comedies in eighth grade classes, and I find my students leaving the unit with excitement about the Bard and having a sense of power in reading new texts in subsequent years.

I’ve chosen to organize these thoughts in ABC order, creating an ABC book of techniques for teaching Shakespearean texts to middle or high school students. This is not a unit plan, and these ideas are not to be taught in this sequence. This is a reference for teachers to pick and choose strategies that will meet specific goals and groups of students, but these ideas are applicable to any comedy, tragedy, or history since the philosophy behind this alphabet book is how to read, and enjoy, Shakespeare.

An Alphabet Book for All

ABC books are given to young children to help them learn their letters. However, creating an alphabet book for a Shakespearean play is a very advanced task, and therefore, any Shakespearean unit could include an ABC book project. Think about any play; what is an aspect of that play that starts with A, with B, with K, with Q, with U…it’s a tall order.

To challenge students to really know a play, you can ask them to maintain or create an ABC book for the entire play. They will have one page, or half page, about a piece of the play that starts with all 26 letters. This will result in students’ understanding, or at least recognizing, 26 different characters, themes, settings, conflicts, etc in the play.

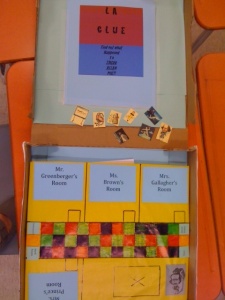

I prefer to make a class alphabet book. I randomly assign each student a letter, and that student must create a two-page spread that closely examines one element starting with that letter, using direct quotes, images, symbols, charts, as well as written paragraphs. Some students choose the obvious topics, like names of characters. However, this project frequently leads to the realization that Shakespeare includes so much more in his plays: weddings, farce, puns, slapstick, animals, arguments, relationships, rivals, violence, and so much more. The unit ends with each class having one detailed alphabet book. (See letter E for more about textual analysis.)

NOTE: This ABC project can be done with almost any subject you may be teaching: chemical elements, math concepts, pieces of the Civil War, musicians, almost anything.

Check back for more of this project; I will post sections of this piece from time to time for those interested in this pedagogy.